This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an inspirational true story about...

Read MoreBlog Page

Will You Help Us? | Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin from the book, Mother of Courage

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an inspirational true story about...

Read MoreThe Best Driver: An Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin’s Determination

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an inspirational true story about...

Read MoreWork Is Work: The Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an inspirational true story about...

Read MoreWe Are the Richer for It: The Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage an Inspirational true story about...

Read MoreMother of Courage: A Real Pearl. The Life of Margaret Chanin

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage an Inspirational true story about...

Read MoreSweetheart of Maimed Veterans: The Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an Inspirational true story about...

Read MoreWaking Up to Courage: The Inspirational True Story of Margaret Chanin

This is an excerpt from the book, Mother of Courage, an Inspirational true story about...

Read MoreThe Relevance of History and the Legacy of Margaret Chanin

Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana is often quoted for his warning: “Those who cannot remember the...

Read MoreMiss Liberty: A Symbol of Strength and Resilience

“Miss Liberty” strides purposefully across the cover of The Saturday Evening Post in September 1943,...

Read MoreTo be blind and yet, to see

Will we ever be color blind? Will we ever be able to construct a society...

Read MoreThe Power of Words

Words have power. The power to harm as well as to heal divide and defeat,...

Read MoreFreedom from Fear

Today, in our time of hurricanes, fires, and floods, of wars in far-off places, of...

Read MoreFreedom from Fear

Today, in our time of hurricanes, fires, and floods, of wars in far-off places, of despair and recrimination and division, it is worth recalling the words of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who recognized the power and the peril of fear.

In his first inaugural address on March 4, 1933, three years into the Great Depression, he asserted his “firm belief that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself — nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

On January 6, 1941, as the country remained on the sidelines of a world war against fascism, FDR returned to the subject of fear in his annual message to Congress. With unity of purpose, he said, a “good society” supports freedom of speech, the “freedom of every person to worship God in his own way,” freedom from want, and freedom from fear — everywhere and anywhere in the world.

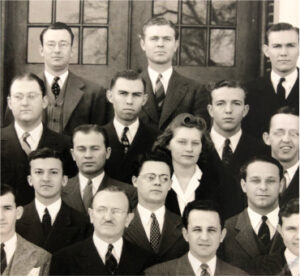

Two years later, a 26-year-old woman without arms delivered her interpretation of FDR’s speech as part of Baylor University’s Wednesday night “Religious Hour”

program. Margaret Jones’ arms were severely burned and had to be amputated when, during a sailing excursion in June 1941, the mast of the sailboat contacted a high-voltage power line. Yet the former dental student returned to school, determined to find, and fulfill, her life’s purpose. The topic of her speech was FDR’s fourth freedom, for as she told a reporter, “I have a speaking acquaintance with fear.”

Margaret Jones Chanin would go on to marry and raise two boys, teach preventive dentistry at Meharry Medical College in Nashville, Tennessee, and become nationally known for her advocacy of people with disabilities. Throughout her life, she embodied a remarkable capacity to breathe in hurt, doubt, anger, and bitterness, and breathe back compassion, calmness, clarity, and joy — both for herself and for those around her. She did not fear change. Rather, she embraced it.

FDR, whose legs were paralyzed by polio in 1921 when he was 39, also knew fear. But, like Margaret, he refused to be incapacitated by it. He was determined to help lead his country through its dark valley of terror.

“Since the beginning of our American history,” FDR said in his message to Congress, “we have been engaged in change — in a perpetual peaceful revolution — a revolution which goes on steadily, quietly adjusting itself to changing conditions … This nation has placed its destiny in the hands and heads and hearts of its millions of free men and women; and its faith in freedom under the guidance of God.”

Freedom of speech and of worship. Freedom from want. And freedom from fear.

A Hill of Beans

In describing her childhood and subsequent life without arms, Margaret Chanin would often say, “Thank goodness for the Depression, or I probably wouldn’t have amounted to a hill of beans.”

By that curious remark, I suppose she meant that growing up during the hard years of the 1930s steeled her for what was to come. They taught her that she had to struggle against seemingly impossible odds if she was to get anywhere in life. But they also aroused in her a deep yearning to help others less fortunate than she was.

Margaret didn’t do it alone, of course. In that dark summer of 1941, when she awoke from a morphine-induced stupor to discover that her arms, badly burned when the mast of her friend’s sailboat contacted a high-voltage power line, had to be amputated, she was surrounded by friends and family who showered her with love and encouragement. The dean of the dental school, where she was a student, insisted that she was going to return to school and graduate. “We’ve got lots of dentists with hands,” Dean Elliott told her. “We could use one with a good head.”

Margaret didn’t do it alone, of course. In that dark summer of 1941, when she awoke from a morphine-induced stupor to discover that her arms, badly burned when the mast of her friend’s sailboat contacted a high-voltage power line, had to be amputated, she was surrounded by friends and family who showered her with love and encouragement. The dean of the dental school, where she was a student, insisted that she was going to return to school and graduate. “We’ve got lots of dentists with hands,” Dean Elliott told her. “We could use one with a good head.”

Margaret’s life unfolded like that of the main character in Winston Groom’s celebrated novel, Forrest Gump, who wondered at one point whether each person has a destiny, or whether “we are all just floating around, accidental, like on a breeze.” Maybe, he concluded, both are happening at the same time.

Margaret was a woman of faith. She believed that God was guiding her path. But she was also courageous. She always walked through an open door into the unknown. She always took advantage of a new opportunity. And because of her pluck and faith, she was able to change her life, and the lives of those around her, for the better.

In an age of cynicism, nihilism, and wanton self-absorption, it is worth considering this child of the Great Depression who, despite experiencing the most severe sort of trauma and loss one can imagine, picked herself up and went on, determined to make a new future for herself, and to become, in her words, worth more than a hill of beans.